Home...

About us...

Legal status...

People...

Projects...

Search this site

...

Reviews...

Podcasts...

Publications...

Media...

Events...

Support our work...

About this site...

Privacy policy...

Contact us

You are here: Home > Publications > Depoliticising Nature

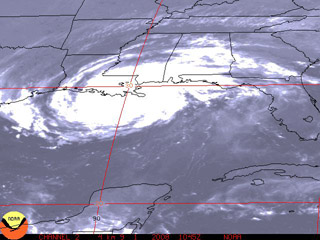

NOTE (added 1 September 2008) As we write this, almost two million people are heading inland from the southern US coastline, fleeing Hurricane Gustav. Readers may be interested in our Hurricane Katrina analysis from September/ October 2005. This article was written at the invitation of, but then spiked by, the openDemocracy website, thereby demonstrating exactly the point that we made below: "The challenge of Katrina is twofold: policy responses that take these lessons into account cannot themselves be simple; and, given the current political dialogue, there is no way these policy responses can easily be aired."

Hurricane Katrina provided the news media with several days of dramatic coverage and human interest stories in August and September 2005. But subsequently, constructive policy proposals were in short supply, as, for political partisans, Katrina was a blank surface on which they could project their own preoccupations. The Left have taken the opportunity to kick against everything that President George W. Bush stands for—in particular to highlight issues of social cohesion, to blame the administration for obstinacy over the Kyoto Treaty and its failure to recognise the reality of global warming, and to criticise the reorganisation of federal emergency management under the Department of Homeland Security. Meanwhile, Bush’s comments, and much of the rhetoric of the administration, have aimed to build confidence in the possibility of reconstructing New Orleans. The "powerful American determination to clear the ruins and build better than before" boasted by the President will offer a shining example of man’s power over nature. The many tens of billion dollars made available as compensation thus demonstrate compassionate conservatism’s care for the people of New Orleans, and the disaster is recast as a triumph. But there are doubting voices such as those of House Speaker Dennis Hastert who raised a thorny question when he stated in an interview that it made "no sense" to spend billions rebuilding a city that lies below sea level. He was shouted down.

In strict terms of policy analysis, Katrina's lessons are simple, indeed commonplace. First, natural disasters happen, and coastal areas in the Gulf of Mexico are at risk whether or not the incidence of hurricanes has been increased by global warming. Second, information is vital to citizens, rich or poor, who wish to look out for their own interests. Commentators suggested that New Orleans was America's "Third World", but if New Orleans really had been in the developing world, patchy or absent communications could have led to deaths on the scale of the tsunami in December 2004. As it was, the approach and course of Katrina were predicted several days in advance, and the vast majority of New Orleans' population successfully evacuated. Third, bureaucratic systems at whatever level of government tend to be inefficient and unresponsive, particularly if corruption is involved, as was notorious in New Orleans: thus they are shown at their worst in a crisis. Fourth, government powers will expand when given an opportunity.

The challenge of Katrina is twofold: policy responses that take these lessons into account cannot themselves be simple; and, given the current political dialogue, there is no way these policy responses can easily be aired.

A system in which the initial responsibility for handling disasters lies at the local level, with escalation to state and then to federal level only if the disaster cannot be handled locally, reflects the view that knowledge and incentives exist locally and that citizens who are able to take the initiative to secure their own safety are the best judges of their own interests. Diffusing that responsibility risks reducing citizens to a condition of passivity and victimhood and enables remote politicians and bureaucrats to evade accountability for their actions and failure to act, both in response to a crisis and when preparing for a crisis. Katrina, however, demonstrated that the sum total of local individual decisions can have disastrous unforeseen consequences, and that therefore collective decisions and actions facilitated by genuine political leadership are vitally necessary. Planning and designing effective responses to natural disasters, and indeed to security issues generally, relies on being able to distinguish between situations where citizens have the correct incentives and can take their own decisions, and situations where individual actions must be constrained in the common interest: any politician trying to forge a democratic consensus on this distinction is bound to face difficulties and tensions, yet this is where leadership must be shown. Equally, detailed planning for disasters must not neglect or undermine America’s main source of strength, identified by Wildavsky:

...[I]t is the institutional structure of nations -- their possession of democracy, market capitalism, and science, rather than any special plan -- that protects them against disasters. (Aaron Wildavsky, But Is it True? A Citizen’s Guide to Environmental Health and Safety Issues, Harvard University Press, 1995: p. 443.)

The New Orleans port complex near the mouth of the Mississippi is the fifth largest port in the world and its essential role in America’s river transport system is central to US market capitalism, along with the petrochemical industry operating in the Gulf which produces about 15% of US-produced petroleum. Such a concentration of infrastructure in any location would be a security vulnerability, but in a location which is prone to hurricanes the threat is likely to be unacceptable. It may now be time to consider the construction of an alternative transport infrastructure such that road and rail can offer an economically-viable alternative to the river system converging on the Mississippi. Energy policies should encourage the exploitation of alternative and renewable sources of energy.

Attempts to enhance a rebuilt New Orleans’s defences against future flooding will merely weigh down the terrain and cause it to sink more quickly into the Gulf of Mexico than it is currently. If New Orleans is not abandoned entirely, the city should be rebuilt in restricted borders on higher ground: a policy that has wider relevance. The popularity of residential development on the coast of the United States has, in the last fifty years, almost doubled population density within a mile of the coastline. This not only puts residents in harm’s way, but also makes the evacuation of a threatened coastline a much longer task in a country whose transport system was designed for the motorist. Federal policy on disasters should proactively limit the creation of new vulnerabilities through more effective land-use planning including restrictions on coastal development, rather than simply providing compensation to victims after the event.

In pursing such policies, Bush must be prepared to take criticism from various constituencies on the right -- those who see the expenditure entailed by the response to Katrina as yet another example of profligacy on the part of the administration, and those who see any affirmation that sometimes nature has humans beaten as an unwelcome concession to the left, leaving Bush open to the charge that the USA should have signed up to Kyoto. Bush should also be ready to face criticism from those on the left whose only answer to the inequality and poverty disclosed by the hurricane is an expansion of the type of welfare programs that inculcate dependency and which will in the long run do nothing to help the residents of New Orleans. Bush’s initial proposal of “Worker Recovery Accounts” of up to $5,000 should be expanded, and the billions saved on reconstructing a city in a doomed location instead put toward relocation grants, money which could be used by individuals to rebuild their own lives. The people of New Orleans deserve better than to be misled with promises that their town and their way of life can be reinstated. Nature makes no promises, and President Bush must be able, despite the political fallout, to say he cannot either.

Transatlantic & Caucasus Studies Institute is a working name of The Transatlantic Institute.

© The Transatlantic Institute 2004-2026. Registered charity number 1108682.